Author: Indigo Curnick

Date: 2024-01-13

Introduction

This essay is in some ways a follow up to a previous blog post about economics. In other ways, it is stand alone. Allow me to explain. You don't have to read that post to understand this one, and this post won't be about economics. A lot of the same ideas are going to crop up and we'll be putting them into a larger epistemological framework.

First, I wish to complete a more general framework of talking about logic. Second, I want to form a defence of extreme rationalism. As part of that defence I will also be dismissing the idea of any kind of empirical logic.

Background to the Problem of Knowledge

The core idea of this article is epistemic justification. Epistemic justification is the capacity to provide some reason to believe a proposition is true. The concern is whether pure reason provides sufficient epistemic justification in some cases.

Bonjour in his A Defense of Pure Reason begins by differentiating between two meanings of a priori

- independent of appeal to experience

- with appeal to reason or pure thought

At this stage of our analysis, there is no reason to suppose these are the same thing. Let's call them the "negative" and "positive" form. First, a far too broad definition of "experience" can render the category of a priori epistemically uninteresting. For instance, to say that you "experience" a mathematical proof when you follow it would eliminate the category of the a priori itself. While it is clear that a person must exist to engage in a priori reasoning, this is not what the concept is trying to get at

This links to the idea of acquisition. Consider one of the popular a priori examples "nothing can be red and green all over at the same time" (now called the red-green thesis). In the red-green thesis there is the issue that unless someone had some experience of "redness" and "greeness" there seems little reason for them to believe the proposition, or even to grasp it. One could limit the definition of the a priori to include only that which contains no reference to anything experiential at all. This is Kant's idea of "pure a priori knowledge". This also misses the point and conflates the ideas of acquisition and epistemic justification. The rationalist position is that no experience is necessary to draw conclusions from the premises, once the premises have been understood. We allow for the possibility that experience was needed to understand the propositions. Consider the favourite example "everything in the universe is or is not a forklift". To grasp this statement, one must have experienced the forklift, but no appeal to experience is necessary to understand the truth of the statement.

Kripke in Naming and Necessity points out a simple fact about a priori reasoning which will be important to keep in mind later, especially when we critique the empiricist-positivist position. Kripke mentions that "a priori" and "necessary" are not the same thing (sometimes "certain" is also used). The concept of the a priori is an epistemological issue dealing with epistemic justification of some proposition. But necessary is a metaphysical concept dealing with existence. As Kripke explains

We ask whether something might have been true, or might have been false. Well, if something is false, it's obviously not necessarily true. If it is true, might it have been otherwise? Is it possible that, in this respect, the world should have been different from the way it is ? If the answer is 'no', then this fact about the world is a necessary one. If the answer is 'yes', then this fact about the world is a contingent one. This in and of itself has nothing to do with anyone's knowledge of anything. It's certainly a philosophical thesis, and not a matter of obvious definitional equivalence, either that everything a priori is necessary or that everything necessary is a priori.

Kant the Empiricist

Before continuing on, I want to delve into more specifics of Kant. In my previous essay Introduction to Economics I used the conception of Kantian philosophy as presented by Hoppe in Economic Science and the Austrian Method. While for that essay the "basic" presentation would suffice, here I want to dig into a deeper issue. The issue concerns Kant's original understanding of the synthetic a priori. As we will see, while Kant is typically considered to be the rationalist of history, his views are actually significantly closer to that of a moderate empiricism.

Kant's original definition of analytic is "the predicate B belongs to the subject A, as something which is (covertly) contained in this concept A". Such a judgement "as adding nothing through the predicate to the concept of the subject, but merely breaking it up into those constituent concepts that have all along been thought in it, though confusedly". In contrast a synthetic (or "ampliative") if "the predicate concept lies outside the subject concept and thus adds something to it". Thus, for example, "all bachelors are unmarried men" is analytic because "unmarried man" is contained within the concept of "bachelor" (or, rather, in this instance, they're the same concept). However, the phrase "all bachelors are lazy" is synthetic, since "lazy" is not contained within the idea of "bachelor" (this is the case whether the proposition is true or not). While this might seem to be rationalist in nature, Bonjour points out this is actually an admission for the empiricist. This, for instance, mirrors the understanding of "analytic" as given by Ayer in Language, Truth, Logic. We will return later to whether this account is in fact as unproblematic as it first seems.

Kant focuses on synthetic a priori knowlede. Now, to the empiricist, such knowledge can not exist. Kant never doubts it. He offers putative examples of the phenomena though. For instance, the most common, 7+5=12. So if anything is a priori, this would be. However, how is this synthetic, not analytic? Kant says that the concept of "12" is not contained within the concept of "5+7". In other words, there's nothing about this union which immediately brings about the concept of "12". Bonjour says this must be true, but offers that a more clear example would be much more complex arithmetic operations. Ones where the concept of the arithmetic problem itself would be obvious, but not the solution. For example, one can grasp the concept of 36,000,145 / 4,987,234 without understanding the concept of "7.218459169952723" (which you can't really even grasp properly due to that not being a complete decimal representation).

Bonjour goes on to argue that Kant's rationalist position is quite undermined by himself. Kant's idea is that synthetic a priori knowledge would not be possible if the "objects that such knowledge purports to describe were independent objects external to the knower, things-in-themselves that are part of independent, an sich reality" In other words, the mind so shapes or structures experience as to make the synthetic a priori propositions in question invariably come out true within the experiential realm. Thus, synthetic a priori knowledge, according to Kant, pertains only to the realm of appearances or phenomena, not to an sich reality.

This mirrors an important distinction raised by Barry Smith in In Defense of Extreme (Fallibilistic) Apriorism. Smith makes a clear distinction between Mises and Rothbard in the understanding of the laws of human action, as Rothbard says

Professor Mises, in the neo-Kantian tradition, considers [the law of human action] a law of thought and therefore a categorical truth a priori to all experience. My own epistemological position rests on Aristotle and St. Thomas rather than Kant, and hence I would interpret the proposition differently. I would consider the axiom a law of reality, rather than a law of thought

Smith makes the Kantian conception of science more explicit

... important epistemological insight to the effect that scientists, if they seek systematic results in the form of scientific laws, must undertake systematic observations guided by relevant scientific assumptions. Kant and his followers have however drawn ontological conclusions from this insight. They claim in fact to have shown that the object-domain which is in each case grasped by the scientist must first have been pre-formed and preconstituted in some peculiar ('transcendental') fashion. This doctrine is then introduced by the Kantians into their explanation of the peculiarity of a priori propositions: the latter are now held to acquire their truth from the fact that we ourselves have in King-Midas-fashion imposed them upon reality, have coerced reality to have it fit our prior prejudices.

What is the alternative, given by Rothbard? As Smith explains

How is synthetic a priori knowledge possible? For the members of the Reinach group, as also for Aristotle, Aquinas and Rothbard, there exists an ontological a priori, an a priori in reality. The a priori status of judgments, propositions, beliefs or 'laws of thought' that is so central to the Kantian approach then proves to be derivative of this more deep-lying a priori dimension on the side of the things themselves.

However, I have personally never read the works of Mises as anything but the more rationalist position as presented by Rothbard. It seems evident to me that the laws of human action are laws of reality, not merely laws of thought. Certainly, a deeper delve into the actual intended position of Mises in Human Action would be worthwhile, but digging into the exegetical questions here is beyond the scope of the current essay.

In conclusion, the conceptions of a distinction between a priori, a posteriori, synthetic and analytic as given by Kant are useful conceptions, it is important to keep in mind that a full acceptance of the originary Kantian view would actually be an empirical position, not a rationalist one.

Empiricist-Positivists Can't Define Analytic

In this section we will be refuting the moderate empiricist position, the ones held by the likes of Ayer. The fundamental issue we will have to deal with in the empiricist-positivist position is how vague they can be with defining terms like "a priori" and "analytic". Furthermore, we aren't critiquing a single position, but rather a broad array of different positions, each of which define "analytic" in some different way.

We will consider "analytic" in the reductive form as given by Gottlob Frege (developed across his whole body of working including e.g. Foundations of Arithmetric) , or Ayer in Language, Truth, Logic. The general conception is something like defining analytic as

- a substitution instance of a logically true statement or

- transformable into such a substitution instance by substituting synonyms for synonyms

Ayer proposes something similar, that a priori truths are mere tautologies. To Ayer, this means they hold no substance, he says

The only other course open to one who wished to deduce all our knowledge from “first principles,” without indulging in metaphysics, would be to take for his premises a set of a priori truths. But, as we have already mentioned, and shall later show, an a priori truth is a tautology. And from a set of tautologies, taken by themselves, only further tautologies can be validly deduced. But it would be absurd to put forward a system of tautologies as constituting the whole truth about the universe. And thus we may conclude that it is not possible to deduce all our knowledge from “first principles”; so that those who hold that it is the function of philosophy to carry out such a deduction are denying its claim to be a genuine branch of knowledge.

Ayer goes on to say

When we say that analytic propositions are devoid of factual content, and consequently that they say nothing, we are not suggesting that they are senseless in the way that metaphysical utterances are senseless. For, although they give us no information about any empirical situation, they do enlighten us by illustrating the way in which we use certain symbols. Thus if I say, “Nothing can be coloured in different ways at the same time with respect to the same part of itself,” I am not saying anything about the properties of any actual thing; but I am not talking nonsense. I am expressing an analytic proposition, which records our determination to call a colour expanse which differs in quality from a neighbouring colour expanse a different part of a given thing. In other words, I am simply calling attention to the implications of a certain linguistic usage.

We call this definition schema reductive since it attempts to reduce a priori statemnts into simpler a priori statements, in this case, the propositions of logic. For instance, if we accept the logical claim "for any proposition P, not both P and not P" (the law of contradiction) is a truth of logic, then we can recognise a priori that "it is not the case that the table is both brown and not brown" is a true statement. The shortcoming is in understanding which propositions count as "truths of logic".

One thing that is important to note here is the Fregian conception actually offers some genuine epistemological insight. Returning to a common example "all bachelors are unmarried men", we can see that we can indeed replace "synonym for synonym" here by turning this into "all bachelors are bachelors". This does offer genuine epistemological insight by transforming some analytic phrases into the form "A = A" (the law of identity).

While this might sound reasonable at first glance, the devil is always in the detail. The first issue that this position has is the appeal to "truths of logic". For instance, we have already seen two such appeals - one to the law of contradiction and another to the law of identity. Which synonym for synonym substitution can be used in "A = A" in order to reduce it to a further truth? It appears to be at the most foundational level already. The second issue raised is how this process takes place - that is, how do I realise that "bachelor" is in fact a synonym for "unmarried man"? This is actually a reskin of the first problem - this is yet another appeal to the law of identity. How do we first justify this law, and then second how do we realise it can be applied?

The solution to all cases, which the empiricist can not admit is the existence of genuine rationalistic insight.

Ayer, is, in fact, partially correct. His examples do actually align with what he is saying. For instance, when he says that “Nothing can be coloured in different ways at the same time with respect to the same part of itself” he is correct that this tells us nothing about the actual colour of the object (if any) in question. My favourite example is "everything in the universe is either a forklift or not a forklift". It is trivial to see that one does not need to know what a forklift is or how one would go about categorising objects as forklifts to see the plain truth of this statement.

However, Ayer does not consider all a priori statements. His view breaks down when we consider a very special set of a priori statements. Those that consider the person making the statement themselves. Once we realise the truth of praxeology and the principles of human action, we can start to find a priori truths that are not mere tautology, or rather, synthetic truths can arise from combinations of mere tautologies. For instance, the statement "one can not argue that one can not argue" does not merely tell us something about how language is used, and is not mere tautology. This self-justifying synethetic a proiori truth tells us something critical about the nature of human actors.

Smith takes a different approach to refute the Ayer position. He asks us to consider the transitive part law which is

If A is a part of B, and B a part of C, then A is also a part of C

Smith also brings up the standard empiricist-positivist definition of "analytic" (which Ayer also subscribes to):

A proposition is analytic if and only if it is either itself a law of deductive logic or it is capable of being transformed into such a law through the replacement of the defined terms it contains with corresponding definitions

An example of where the empiricist-positivists can apply this definition is in the well known toy phrase "all bachelors are unmarried men". Ultimately, in this phrase we can always replace "unmarried men" with the equivalent term "bachelors" to produce the (still correct) statement "all bachelors are bachelors". Even the empiricist-positivists would not go so far as to deny that all bachelors are indeed bachelors (that is not to say that there are not some who would question this).

However, if we return to the transitive part law, there is only one phrase within it which could reasonably be replaced which is "is a part of". However, since this is the only phrase that could be replaced, any replacement of it would not actually be revealing of anything. The reason why it works in all bachelors are unmarried men is that we are putting one idea in terms of another idea. One idea can not be merely placed in terms of another in the transitive part law. Thus, by the empericist-positivist definition, the transative part law must be synthetic.

However, which experiments, precisely, could be used to measure the truth of the transitive part law? We could do something like place a stone in a bucket, and place that bucket into an even larger bucket. Certainly, this is a demonstration of the transitive part law, but notice how the transitive part law itself had to be assumed to form this experiment in the first place. For a start, an appeal to the definition of "is a part of" had to be made. Secondly, an appeal to placing the stone inside the even larger bucket had to be made in placing the bucket into the even larger bucket, since it already contained the stone. You even have to make an appeal to the law to demonstrate that the stone is indeed inside the even larger bucket. In other words, we have this synthetic a prori law that isn't mere tautology which tells us something about the real world!

Does Empiricism Require any Non-Empirical Assumptions?

Most contemporary philosophers have come to answer "no" to this question. The current vogue has been that empiricism requires nothing of rationalism. Commonly cited philosophers who answer "yes" include the archrationalists Ludwig von Mises, Murray N. Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Lionel Robbins, Martin Hollis, Edward J. Nell and others.

Smith points out that

To carry out experiments in meaningful and systematic fashion, to represent the results of these experiments theoretically, and to process these results, one needs assumptions, concepts, categories and other theoretical instruments. Logic and the theory of definition, as well as many branches of pure mathematics, belong to this pre-empirical foundation of the empirical sciences - 'pre-empirical' in the sense that it cannot be gained through induction or observation but rather makes induction and observation possible.

In other words, at least some degree of philosophy of science needs to be done before science itself can be done. Philosophy of science, though, has no empirical tests.

Can we elaborate on Smith's brief position? There are several axiomatic foundations upon which experiments rest. First, all experimentation requires the assumptions of causality, that is, the capacity for event A to cause event B. Without this, it would not be possible to draw any conclusions from experiments. At best, you could say "today I did A and observed result B". To move from a history of repeated trails to a concrete conclusion "A (may) cause B under circumstances C" requires the axiom of causality. As Mises says

The natural sciences too deal with past events. Every experience is an experience of something passed away; there is no experience of future happenings. But the experience to which the natural sciences owe all their success is the experience of the experiment in which the individual elements of change can be observed in isolation. The facts amassed in this way can be used for induction, a peculiar procedure of inference which has given pragmatic evidence of its expediency

What experiment could one use to prove that causality exists as such? Even putting aside the fact that using empirical methodologies to prove the capacity of empirical methodologies is question begging, experimental design to demonstrate the existence of causality would itself require an appeal to causality.

The next foundation upon which experimentation rests is that of a uniform or constant laws of nature. It was the early Christians who popularised this idea - that God created uniform laws of nature which it was possible to discover. Before this, pagan ideas of almost random happenings precluded the capacity for scientific discovery. Now, this idea is far more than a Christian one, but an axiom of pure science. Without this axiom, you again could only at best record history i.e. "today I did A and then saw B". Since the laws of nature might change, you can not draw any inference from these. Perhaps today it behaves one way, perhaps tomorrow another. Again, the capacity to design an experiment to demonstrate the constancy of the laws of nature requires an appeal to the constancy of the laws of nature.

A good way to think about this is to consider any experiment from physics. If we consider, say, the Millikan oil drop experiment for measuring the charge of an electron, each time Millikan (or any physics undergraduate) finds an electron on an oil drop, we can be sure of one thing: the electron has the same nature and properties as any other electron. If every electron had some random charge, this experiment would yield nothing of value, but a journal of specific electrons to specific charges. It is only from this fact that the universe has a nature which can be discovered can this experiment tell us anything of value.

As a side application of this principle, we can see the epistemological issues which are present in psychology experiments. Unlike electrons, people are not all the same, and for the variables and parameters of the experiment, this makes a huge difference. Even the same person on different days has different knowledge and experience, and hence behaviour. In this way, it is very very challenging in psychology experiments to ever move from a journalistic record (called "case studies") to any solid, scientific conclusions.

The next foundation of importance is the appeal to categories and original definitions. If designing an experiment to prove that 1+1=2, then we would need to ask how specifically we could do this. Perhaps you do something like get one stone, then another stone and then bring them together to find two stones. While this might seem reasonable at first glance, the issue is you must first appeal to the definition of "1" to get one stone, and have a rational insight to comprehend that you do indeed have one of an object. Then in the union of the stones, again a rational insight is needed along with an appeal to the definition of "1+1=2" to recognise the union as the addition. Even designing the most basic experiments to test even the most basic propositions require appeals to, and the use of, rational insight to draw even the most foundational conclusions.

The final foundation I want to touch upon is the very idea of inference itself. Contrary to the presentation of the empiricist-positivists, in science you do not only make observations. It is much more than that - you must draw conclusions. The making of observations is mere history or journalism, while critical to the scientific process, offers little more than a record of events. Even an experiment as simple as proving a coin is fair requires drawing conclusions from observed events. Suppose you flip a coin 1000 times and note the results. First, even something as simple as counting the heads and tails makes an appeal to cateorisation and bijection. Then, in finding 500 to be heads and 500 to be tails, it takes further appeals to probability theory to move from this "simple" observation to the "simple" conclusion that the coin is fair.

If we take this idea further beyond science, Bonjour refers to it as "intellectual suicide". Even consider the simplest syllogism

- P1: All P are Q

- P2: P

- C: Therefore, Q

Without some appeal to rational insight, it seems impossible to justify the move from P1 and P2 to C.

Is Logic Itself Empirical?

Putnam raises several arguments that logic is in fact empirical in Philosophy of Logic and Is Logic Empirical. Let's summarise them first.

We generally think of logical truths as a special case of necessary truths, but Putnam points out that we now reject certain claims which were once thought necessary. Claims about straight parallel lines in geometry are now not only considered maybe false in some circumstances, but that they are in fact false. We note again that Kripke points out that a priori truths and necessary truths are often conflated - they are not even of the same "kind" of truth.

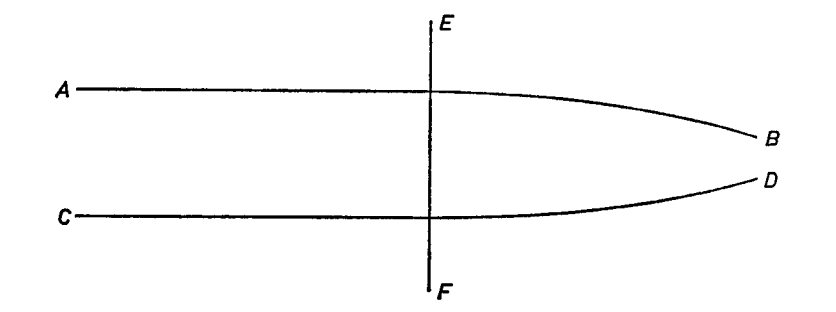

Consider the following diagram. To the left of EF we sit in a Euclidean space, where the lines are parallel. To the right, non-Euclidean space (maybe these are two beams of light traveling through space that come close to a gravitational source).

A physicist claims that both of these are straight lines. Does this not break our classical logical intuition of what "straight lines" are? Putnam presents three hypotheticals which appear to break logic

- Someone claims that AB and CD are both "straight lines"

- Someone claims that he has a sheet of paper which is scarlet (all over, on both sides) and green (all over, on both sides) at once

- Someone claims that some men are married (legally, at the present time) and nonetheless are still bachelors

Putnam points out two things. First, 1 seems to be true for empirical reasons. He also points out that in a classical logic, neither 1 nor 2 actually contains a contradiction of the form "P and not P". He also points out that unless you stipulate that "Bachelor is an unmarried man", neither does 3 contain such a contradiction.

Claim 1 is rather easily dismissed out out pocket - "straight lines" has a very specific definition to a physicist which might not be the same one that every day people would have. This is nothing more than terminological confusion. Claim 2 supposedly contains the issue that it does not contain a contradiction of the form "P and not P". Putnam fails to realise that there are simply other possible ways that something can be false than contradiction. And 3 is especially bizarre - sure if "bachelor" and "unmarried man" happen to be meaningless phrases that are not related to reality in any way this phrase carries no meaning. The phrase "gzorpazorps are florplecells" is meaningless in this way. However, by convention (of course, it could have been otherwise), "bachelor" and "unmarried man" do have meanings. Even if language had not been made to express the concepts the concepts would still exist. The concepts are not the language that represents them. Much like Ayer and Frege, Putnam again falls into the trap of confusing the epistemological issue of a priori with the metaphysical issue of necessary.

Putnam also uses quantum mechanics (QM) in an attempt to demonstrate an empirical nature to logic. He points out that following situations could arise.

First, we establish that

(\(A = a_1\) or \(A = a_2\)) and (\(B = b_1\) or \(B = b_2\))

is true.

Then, via some Hilbert space formulations (let's not concern ourselves with mathematics and just accept it as true) we find that

(\(A = a_1\) and \(B = b_1\)) or (\(A = a_1\) and \(B = b_2\)) or (\(A = a_2\) and \(B = b_1\)) or (\(A = a_2\) and \(B = b_2\))

is false. It seems as though we need to change our logic system for empirical reasons. In other words, the distributive nature of classical logical statements, specifically, seems off in QM

Kripke gives a two pronged refutation of Putnam. First, he gives a specific refutation of the argument that logic needs to be changed due to QM and the second is a broader refutation of the idea of an empirical logic.

Let's start with the specific refutation.

Kripke begins with a particle which has some position \(S\), which we know. Let's suppose this particle, as all particles do, has some momentum \(T\). The question is, what is the value of \(T\)? For every conjugation of \(S\) with \(T_j\) will be false at this stage, that is \(S\) conjugate \(T_1\) is false, \(S\) conjugate \(T_2\) is false, \(S\) conjugate \(T_n\) is also false. So, we might say \(S\) conjugate \((T_1, T_2, ... T_n)\) is false. Kripke points out the subtlety here. The second form might seem to be equivalent to the first, but now what we are effectively saying is "the particle has no momentum", but we know it does (if we take a measurement, we will get one).

In other words, let's return to Putnam's original scenario. If

- \(A = 1\) or \(A = 2\)

- \(B = 1\) or \(B = 2\)

If both 1 and 2 are true then

- \(A = 1\) and \(B = 1\)

- \(A = 1\) and \(B = 2\)

- \(A = 2\) and \(B = 1\)

- \(A = 2\) and \(B = 2\)

(3 and 4 and 5 and 6) as a set is false, but we need to keep in mind why this is. We know that at least one of them is true. Actually, in this case, we know there is always precisely one value which is true. There's enough information in 1 and 2 to show is this, but not enough information to show which of 3, 4, 5, 6 is true.

If I might expand on Kripke here, QM is defined by uncertainty. In every day life, we can be pretty sure of the state objects are in, and if we are not we can simply make a measurement. In QM, the systems are so small any measurements we make can greatly disturb the system in such a way as to cause it to change significantly.

Imagine you are trying to measure the temperature of the room. You use a thermometer, of course. However, technically, the thermometer, in making its measurement, will remove some of the energy from the room thus impacting the room's temperature. This is no big deal though, since the amount of energy the thermometer might be able to take from the room is virtually zero in comparison to the room's.

Imagine now that you are trying to measure the momentum of a single atom. Any apparatus that you devise to do this is going to have to alter the momentum that, ultimately, your affect on the system will be much, much greater than the original momentum in the system to begin with.

In classical physics you might do the cannon ball problem. It would go something like a cannon ball is fired from X at angle Y with velocity Z, where will it land. Imagine, instead, the problem was something like: a cannon ball is fired somewhere between A and B, with angle somewhere between C and D and with velocity somewhere between E and F. You simply would not have enough information to come to a definitive answer on where the cannon ball would land. However, you could find the maximum and minimum locations the cannon ball could land - in other words you could say it will land between G and H.

Another way to think about this is in logic we might say something like "nobody can be both married and a bachelor". The definitions of married and bachelor are mutually exclusive. Now imagine John: I have no idea if John is married or not. It's a totally reasonable thing to say "John is either a bachelor or he is not a bachelor". I don't know which, but one of those options must be true. To suggest that I might need to adjust logic because I don't know enough information about John here would be absurd. The issue lies not in the logic, but in our capacity to gather enough information about the real world to apply that logic. Truly, everything in the universe is either a forklift or not a forklift.

Looking at Kripke's second point now on the impossibility of adopting a logic. Allen Stairs in Could Logic be Empirical? The Putnam-Kripke Debate found in Logic and Algebraic Structures in Quantum Computing says

Kripke’s larger point is that there is a problem at the core of Putnam’s view. Putnam, he thinks, believes that we could somehow decide to “adopt” a logic; Kripke insists that this is incoherent. We misunderstand logic if we think there are “logics” among which we could somehow choose. There is reasoning. Specific formal systems may or may not adequately capture aspects of correct reasoning. But there is no neutral place outside logic from which to decide what “logic” to adopt.

Which is, I think, perfectly put. If one was to empirically assess some logical system and then adjust our reasoning, we would need some kind of neutral reason and logic to make the decision. Thus, the question is raised: how did you empirically decide on that system of logic to use to determine which system of logic to use? And then, how did you empirically decide on that system of logic to use to determine which system of logic to use to determine which system of logic to use? And then, how did you empirically decide on that....

However, the keen eyed might notice that in some way Kripke and I have introduced a potential flaw into the rationalist approach. How do we justify our reasoning? Kripke does vaguely imply the solution - he talks of a difference of some formal logic system and reasoning, which is somehow more fundamental. Reasoning plays the part of the "neutral" system with which we can evaluate formal logical systems. With which system of reasoning do we assess this reasoning?

We're already discussed quite extensively the solution to that problem - we invoke the capacity for rational insight. We also can, through praxeology, offer the existence of the synthetic a priori proposition, of which more details can be found in Introduction to Economics.

As such, broadly, human reasoning is done through the method of synthetic a priori statements. Sometimes, we can use good old analytic a priori statements i.e. "You can not be married and a bachelor" (given that bachelor means not married). Much of classical formal logic actually proceeds via analytic a priori systems, but it is the human capacity for synthetic a priori statements to evaluate meta-logic, and meta-meta-logic, and meta-meta-meta-logic, and meta-....

Perhaps a bone can be thrown at the empiricists. Ultimately, this does depend upon us: humans, real humans in the real world. We are "empirical" beings, in the sense we are flesh and blood. Perhaps there is some divine being which grasps all a priori truths without need for synthetic argumentation by its very nature. However, we are not that. This links quite strongly to my view that a priori truths are "out there" waiting to be discovered. I liken this to an astrophysicist discovering new galaxies. The galaxies are "out there" and need to be discovered, by constructing new telescopes. In the same way a priori truths are "out there" (not physically, but they already exist in a sense) and we discover them. Except, we don't engage in empirical experimentation but thought experimentation.

Actually, I think this also neatly completes the essay by Stairs. He says

Even if we grant that there’s no place to stand outside reasoning, there’s a more general phenomenon here. What William Alston called doxastic practices typically have the sort of self-supposing quality that Kripke’s point relies on. We can reconsider how to evaluate beliefs based on sensory input; when we do, we’ll need to rely on at least some such beliefs and hence on the practice of forming beliefs based on sense evidence. We can consider what memory can and can’t teach us; we can’t avoid relying on at least some memories when we do. Equally important, these practices aren’t insulated from one another. In considering what weight to give memory, for example, we’ll make use of claims that we’ve accepted on the basis of the implicit and explicit rules/practices we use for assessing other kinds of empirical claims. We can also reason about how to reason, as Kripke would be the first to insist. Putnam may seem to be saying that we can evaluate logic without relying on logic broadly conceived (i.e., on logic qua reasoning) but it’s not clear that he means this or needs to say it. In order to rebut a measured version of Putnam’s view, Kripke would have to show that reasoning is the one doxastic practice to which the deliverances of other doxastic practices are irrelevant. Putnam’s larger point would be made if sometimes what we discover empirically can properly enter into our deliberations about how to reason.

Indeed, the "most fundamental" doxastic practice is the self-justifying synthetic a priori method of reasoning.

Now, I want to return to some of Putnam's earlier arguments on geodesics. Kripke doesn't address these (he goes right for the kill in QM), but I want to look at them now for completeness.

Consider the following conversation

Alice: "If today is Tuesday, then tomorrow is Wednesday"

Bob: "Ah but tomorrow is Friday, so classical week logic is wrong!"

Alice: "Ok, but today is Thursday, not Tuesday"

What mistake has Bob made here? I trust you see that Alice is correct on both counts. Indeed, if today is Tuesday, then tomorrow must be Wednesday. Equally, if today is Thursday, then tomorrow is Friday. Even if today is Thursday, I can still correctly make the statement "If today is Tuesday, then tomorrow is Wednesday".

We must question what happens in the line EF that causes the parallel lines to begin to converge. Putnam totally glosses over this. A real life example might be two beams of light traveling parallel through space. They then encounter some mass, causing them to bend. Does the fact of convergence after the conditions have changed "disprove" the parallel lines before the conditions changed? This is obviously false.

To be more abstract, let us consider this diagram again. On the left of EF we are in a euclidean geometry regime and on the right we are in a non-euclidean geometry regime. Clearly, in the first straight, parallel lines will never converge. On the right, clearly, straight parallel lines can converge. Think about the surface of the earth – two lines which are parallel at the equator will converge at the North pole. Putnam says that it is intuitively clear that this is a contradiction. Why? There is no contradiction here at all. In one regime we have one set of contingent truths, and a different set in another regime. The "logic" of parallel lines not converging is true on a flat plane. Putnam is presenting it as though the "logic" of parallel lines not converging is true globally and when he finds an example to the contradiction, declares that logic is empirical, fake or otherwise made up. This is no refutation whatsoever, of course. What Putnam would need to do for a real refutation is find an example of straight, parallel lines converging in a Euclidean geometry scenario. Of course, he can not.

There is another broad point Putnam is getting at however. Perhaps it can be categorised as a historical perspective. Consider a person from a long time ago, they would perhaps agree that indeed there are no situations under which parallel straight lines can converge. The reason for this is that non-Euclidean geometry had simply not been discovered at that time. This perspective is that logic is not some universal concept but rather a human tool. This would put it in the same kind of category as the screwdriver – something that is incidentally useful to humans. In this scheme, logic is considered empirical since it is continually refined and updated. This is also an abortive attempt to show that logic is empirical.

The issue with this historical perspective of logic is that it assumes a kind of idealistic projection of the human mind onto the universe. Consider the parallel lines on the surface of the earth again. Eventually they converge at the North pole. The historical perspective of logic would have us believe that until "the human mind" "decided" that non-Euclidean geometry is an "incidentally useful" tool this would not be possible. After all, if it is the case that non-Euclidean geometry "works" "in the real world" before it is "invented" by "the human mind" then this perspective totally falls apart. Since, that would mean, that there is a greater universalism to logic than the historical perspective would allow.

In fact, we clearly understand that non-Euclidean geometry "worked" before it was discovered. The fact that humans can be mistaken about something or other has no bearing on logic qua logic. Consider a simpler example – "A is A". This is likely the simplest logical axiom. The historical perspective of logic would be that until the first human was born who declared that "A is A" (purely for utility reasons, of course) then something being itself was not necessarily true. Things could be not themselves, or themselves, or something else entirely, until the human mind warped reality to suit itself.

Of course, I also here disregard the perspective that now things are not themselves. The position that "A is not A" is not worthy of entertaining. After all, in order to begin to make the argument that "A is not A" one must first find some A to discuss. But what is that concrete A if it is not itself?

In other words, a human actor can not even begin to make the argument that "A is not A" without first assuming that they are themselves i.e. that "A is A" is actually true. In short, any attempts to disprove "A is A" actually only serve as a refutation of the very abortive argument attempting to be made.

All of this is to simply say this: the fact that humans can continually discover more logic has no bearing on the operation of the universe. In other words, logic already exists and we aim to discover it. The universe is not created as a blank slate in which we invent and enforce whatever logic is convenient to us onto it.

Could Knowledge be Hermeneutical in Nature?

Hoppe deals with this question in In Defence of Extreme Rationalism: Thoughts on Donald McCloskey's "The Rhetoric of Economics". In this essay, Hoppe critiques McCloskey's[1] work which proposes a hermeneutical interpretation of economics.

The hermeneutical position is that epistemologies are frameworks proposed to facilitate social cohesion rather than there being a "truth" to which they appeal. In other words, epistemology is a mere arbitrary social game rather than some scientific inquiry. As McCloskey says

[The categories truth and falsehood play no role in this endeavor. Scholars] pursue other things, but things that have only an incidental relation with truth. They do so not because they are inferior to philosophers in moral fiber but because they are human. Truth-pursuing is a poor theory of human motivation and non-operational as a moral imperative. The human scientists pursue persuasiveness, prettiness, the resolution of puzzlement, the conquest of recalcitrant details, the feeling of a job well done, and the honor and income of office. . . . The very idea of Truth—with a capital T, something beyond what is merely persuasive to all concerned—is a fifth wheel. . . . If we decide that the quantity theory of money or the marginal productivity theory of distribution is persuasive, interesting, useful, reasonable, appealing, acceptable, we do not also need to know that it is True. . . . [There] are particular arguments, good or bad. After making them, there is no point in asking a last, summarizing question: "Well, is it True?" It's whatever it is—persuasive, interesting, useful, and so forth. . . . There is no reason to search for a general quality called Truth

McCloskey is certainly on the mark when claiming that "Truth-pursuing is a poor theory of human motivation". At least this I can agree with - it is a great shame that only a small number of intellectuals actually follow the scientific principles of searching for truth, whilst all, of course, appeal to it for authority. Nevertheless, it is critical for at least some of us to adhere to the idea of Truth. Certainly, it is worthy of pursuing Truth for its own sake. Ultimately, in science, there is no other mark nor measure.

Hoppe points out that if we take McCloskey seriously, and seriously claim that there simply does not exist any objective Truths to which we can measure and appeal, and that everything is mere social games, then they are defeating the purpose of their own argument. We only have to ask "what if we apply their own ideas to their own ideas"? At this point, they are saying nothing about nothing. Ultimately, one can not argue that one can not argue.

Hoppe concludes

Thus, if McCloskey were right and there were indeed no objective truth, he could not even claim to entertain anyone meaningfully with his book. His talk would be meaningless, indistinguishable from the rattling of his typewritter [sic]. He would advocate even greater intellectual permissiveness than first thought. Not only would he have to drop the distinction between truth-claiming propositions and propositions that merely claim to be entertaining, but his permissiveness would go so far as to disallow any distinction between meaningful talk and a meaningless assemblage of sounds. For one cannot even claim to entertain with talk that involves no truth-claim beyond that of being meaningful talk, without still having to know what objective truth is and be able to distinguish between truth-claiming propositions and those statements (for example, in fictional talk) that do not imply any such claim.

In fact, the hermeneutical position of talk for talk's sake, of contributing anything and everything to the conversation of mankind so long as it is persuasvie is self-defeating in a very extreme way. McCloskey makes the claim that certain ethical foundations are necessary for the great conversation to take place, from the smaller "don't lie" to the more extreme "do not resort to violence". However, since in the hermenutical epistemology nothing can be said to be true or not, only convincing, what if I remain unconvinced by these statements? In that case, the easiest refutation of the hermenuticals is to simply kill them. After all, without any means by which one measures truth, how can it be objectively claimed one way or another if killing the hermenuticals impairs the conversation of mankind in any way?

McCloskey spends some time in The Rhetoric of Economics defeating the empiricist-positivist position. This misses the mark in a few ways. First, the true opposition to the hermenutic position is not the empiricist-positivist position, which can be seen as a kind of side-step, but rather the rationalist position. Second, defeating the empiricist-positivist position does not lead one to the hermenutic position. In fact, it is the archrationalists (such as Mises, Rothbard, Smith and so forth) which have leveled the most devastating critiques of the empiricist-positivist position.

Hoppe first points out that empiricism is a methodological monist theory in a sense. That is, there are predictions and nothing else. McCloskey makes the claim that predictions in economics is impossible. Thus, in order to crack the monist empiricist position, McCloskey would need to be able to do two things. First, demonstrate that there is a methodological dualism - that predictions are possible in some domains but not others. And then to demonstrate why such predictions are possible in some domains but not others. McCloskey does not attempt to do this.

Hoppe says

Empiricism is observational monism, stating that all our empirical knowledge is derived from observations and consists in interrelating these observations; and, further, that observations as well as relations have the permanent status of only being true hypothetically. This is the case in economics as well as in any other field concerned with empirical knowledge, and hence the problem of prediction must be the same everywhere. McCloskey does not answer this systematic challenge. He does not present the conclusive refutation of such monism by pointing out that in claiming what empiricism claims, one in fact falsifies the content of one's statement. For to claim what it claims, empiricism must actually presuppose that in addition to observations, meaningful objects exist—words tied to reality via cooperation—that, along with the relations among them, must be understood rather than observed. Hence the need for methodological dualism.

Hoppe then goes on to point out the impossibility of scientific progress under the empiricist doctrine. Since empiricism relies on prediction and causality as the movers of scientific knowledge, yet does not allow for methodological dualism, then one is left in a situation where the concept of prediction and concept of causality themselves are also empirical claims. This, of course means, that they are never truly known and subject to endless testing. The consequences of this is that we can never really know that prediction and causality are indeed real and possible. Furthermore, and even more sinister, it is conceptually almost impossible to design some experiment to measure prediction and causality. What is the point in any other experiment if prediction and causality are mere hypothesis never known to be true? Without these foundations of prediction and causality, any experiment is nothing more than a mere journal entry - unifying it into a grander theory about reality is impossible.

The solution which the empiricists can not admit is that there is a methodological dualism which allows for the introspection to realise the systems of prediction and causality without observation i.e. from axiomatic, rationalist principles. And in fact the hermeneutic principles outlined by McCloskey fails to generate this foundation for prediction and causality as empiricism but for different reasons. In hermenutics there is just talk and talk for talk's sake. Ideas like objective causality simply do not exist, since again, in order to do this hermenutics would need to admit methodological dualism.

How then, does rationality prove the existence of causality? The fundamentals is that science must be done by human actors. In order to theoretically prove the existence of causality by the empiricist claims one would need to set up some kind of experiment to observe some kinds of events can not be observed or produced without earlier interference. Yet notice how in order to even conceptualise this experiment one would have to admit whole-heartedly already the principles of causality. After all, an experiment is nothing more than an observation of cause and effect. The concept of causality is baked into the concept of experiment. One can not be an empiricist without implicitly admitting the rationalist axioms of causality. Quite ironically, it is the empiricists themselves who provide the most iron-clad proof of the rationalist axioms.

Hoppe brings up one more point about McCloskey's hermeneuticism. He points out that hermeneutics is an outgrowth of literary interpretation of the Bible. Thus, the idea of accepting theories as correct based on authority is baked into the hermenutic DNA. While this is a very acceptable, useful and correct system of proof in organised religion, it is quite out of place in science. McCloskey's point is that empiricism was correct when it was fashionable. Now, that empiricism is no longer fashionable, it is no longer correct. Again, the relativistic assumption is that objective reality does not exist and can not be measured, and even if it did exist, there would be simply no value at all in measuring it correctly.

Hoppe uses the example of the law of supply and demand to demonstrate this principle. I won't repeat the entire theory here, as I have already covered it in my previous economics articles. It is important to note that while Hoppe works through a specific example, this would apply to any synthetic a priori statement, not just one from the specific field of economics. While in other works Hoppe has refuted empiricism in terms of fundamental theories of economics, he here extends this to the hermenutic theories. McClokskey, for instance, claims a hermenutic justification for the law of supply and demand, claiming it is persuasive due to a "socialisation" in the field of economics, and an authority argument that many foremost economists believe in it. However, this raises the question immediately of how the law is justified if one were not socialised in economics. Frankly, the McCloskey viewpoint is the law is true or not true depending on whether the person reviewing the law was correctly or incorrectly socialised (i.e. brainwashed) into believing it. How do we justify whether the "socialisation" McCloskey discusses is good or bad? Certainly someone could be socialised to believe any number of different competing views on the law of supply and demand - the question is how we shift through these to find the correct one.

In conclusion Hoppe says

Empiricism recommends the law of demand because it supposedly looks good—yet we can neither see it, nor would it survive empirical testing. Hermeneutics, on the other hand, recommends it because it supposedly sounds good—yet to some it sounds bad. And without some objective, extralinguistic criterion of distinguishing between good or bad, it is impossible to say more in support of the law of demand than somebody said so.

Austrians, as should be clear by now, have no reason to take either the old empiricist fashion or the new hermeneutical one very seriously. Instead they should take more seriously than ever the position of extreme rationalism and of praxeology as espoused above all by the "doctrinaire" Mises, as unfashionable as such a stand might now be.

Notes

[1] Donald McCloskey is now known as Deirdre McCloskey, a transgender woman. I will use the original publication author name where to avoid referential confusion. When quoting Hoppe, I will not edit the original quotes in their use of "he", to preserve Hoppe's original work.

References

Kripke, S. (1972) Naming and Necessity. Harvard University Press

Stairs, A (2016). "Could Logic be Empirical? The Putnam-Kripke Debate". Chubb, J., Eskandarian, A., Harizanov, V. Logic and Algebraic Structures in Quantum Computing. Cambridge University Press

Putnam, H. (1968) "Is Logic Empirical?". Cohen, R., Wartofsky M., Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol 5. Reprinted as Putnam, H. (1975) "The Logic of Quantum Mechanics". Putnam, H. Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol 1. Cambridge University Press

Putnam, H. (1972) Philosophy of Logic. Routledge.

Hoppe, HH. (1989) In Defence of Extreme Rationalism. The Review of Austrian Economics, vol 3.

Curnick, N. (2023) Introduction to Economics. Available online at https://indigocurnick.xyz/blog/2023-10-01/introduction-to-economics

Smith, B. (1996) In Defence of Extreme (Fallibalistic) A Priorism. Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol 12, no 1

Hoppe, H.H. (1995) Economic Science and the Austrian Method. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Kant, E. (1781) The Critique of Pure Reason

von Mises, L. (1949) Human Action. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Ayer, A (1936) Language, Truth, Logic. Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Bonjor, L (1998) In Defense of Pure Reason. Cambridge University Press.